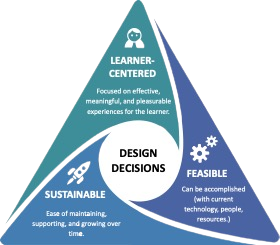

There are three key lenses for great instructional design that also guide learning-design thinking and decision-making:

- Learner-centered: Focused on effective, pleasurable, and meaningful experiences for the learner;

- Feasible: Can be accomplished;

- Sustainable: Easy to maintain, support, and grow over time.

Figure 2. Three lenses of learning innovation for instructional design, modified from The Three Lenses of Innovation (Kelley & Kelley, 2013).

Learner-Centered

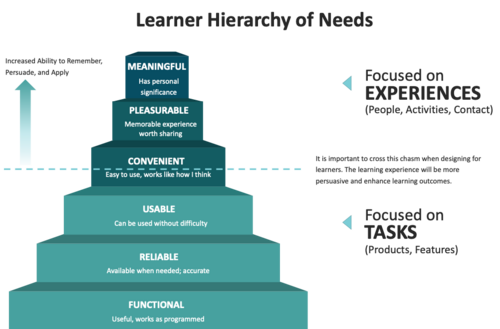

To be learner-centered is to design while focusing on fulfilling the learner’s needs and desired outcomes. In Seductive Interaction Design (2011), Stephen Anderson describes the “Learner Hierarchy of Needs” (see Figure 3). As in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1943, 1954), the base of the pyramid is essential and must be present to successfully support the next level. Once an individual fulfills one level, they look to the next level of fulfillment. For example, in the Learner Hierarchy of Needs, learners need to log in (functional), but they also need the site to have excellent uptime (reliable). When designing for learning, many may stop at “convenient”—meaning that students can log in reliably, they can use the course without difficulty, they can find what they need, and they know where to submit assignments. Students can even use the course across multiple devices and access it anytime, anywhere: it is convenient for their lifestyle. Indeed, these are all important and fundamental aspects of excellent, learner-centered experiences.

But the pleasurable, meaningful experiences represented by the top two levels of the hierarchy are where real transformation in identity and outcome occur. The exceptional instructional design never stops at convenience; it continuously strives toward pleasurable, meaningful learning.

To achieve exceptionality in design, designers must push for all levels of the learner hierarchy of needs to be met, stretching toward designing for those top tiers of the pyramid when creating assessments and activities and tailoring the structure for effectiveness. It is in striving for effectiveness (the ability to achieve learning outcomes) that designers draw upon theory and understanding of human learning, motivation, and key principles of instructional design.

For learning design to be effective, there must be solid instruction, activities, and opportunities for specific feedback, valid assessments, and clear objectives and outcomes, with strong alignment among them all. To be meaningful, the learning design should be relevant, authentic, and connected to students’ lives (which requires designers to know who learners are). To be pleasurable, the experience should lead learners to experience moments of pride, joy, or connectedness (to name a few positive results). All of these aspects of effectiveness require empathy with regard to learners, where they are, and where we want them to be. Most instructional design work resides in the “learner-centered” lens, but it should not stop there. To be exceptional, the second and third lenses must also be employed in practice.

Figure 3. Modified learner hierarchy of needs (based on Anderson, 2011, p. 12).

Feasible

What designers conceptualise should be possible. This second lens of feasibility also means that when innovating, new ideas should not be discarded simply because they have yet to be tried. If the innovation is learner-centered and grounded in how people learn, and if the idea is feasible to accomplish given the context, it can be implemented and tested through a design thinking process.

Sustainable

Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. In other words, just because something is feasible, that doesn’t mean it is sustainable. Ideas can be learner-centered and feasible, but if an idea or design is not sustainable over time, it likely is not the best choice for learners or those responsible for facilitating it. Determining sustainability requires a deep understanding of and sensitivity toward context. For example, in one instance a group of instructional technologists may not have the capacity to edit and maintain certain types of interactives, whereas other groups may have the expertise, funding, and capacity. Each situation requires consideration of context when making design decisions, as decisions made now have both positive and negative ramifications over time.

New modes of course delivery and emerging technologies have put pressure on both higher education institutions and instructors to design courses that are optimised for new forms of instructional communication and interaction. More courses are being delivered online or in hybrid form, and today’s students expect to be engaged in instruction using the same channels of communication as they use in their daily lives.

This calls for a more structured approach to course design, development, delivery, engagement, and assessment.

And this is where today’s instructional designers add value to the challenges of today’s higher education experience, by designing and developing online courses.

What is online course design and development and what does it involve? It includes

Watch this video on Instructional Design to learn more.[Watchtime: 4.59 mins]

ARVE error: maxwidth:

425pxis not validby Commonwealth of Learning

It is essential to distinguish between process and model before we proceed to look at different models of Instructional Design.

Process vs. Models

Instructional design is a process that helps in the design, creation, and delivery of instructional resources, experiences and courses. For instructional design purposes, a process is defined as a series of steps necessary to reach an end result. Similarly, a model is defined as a specific instance of a process that can be imitated or emulated. In other words, a model seeks to personalise the generic into distinct functions for a specific context. The progression of analysing, designing, developing, implementing, and evaluating (ADDIE) forms the basic underlying process (illustrated in Figure 1). Thus, when discussing the instructional design process, we often refer to ADDIE as the overarching paradigm or framework by which we can explain individual models. The prescribed steps of a model can be mapped or aligned back to the phases of the ADDIE process.

Models

Instructional design models provide guidelines or frameworks that help to organise structures of procedures in designing and developing instructional activities. From a designer’s perspective, various models can be used in the instructional design process only to the extent that is manageable for the particular subject and context. Most of the current instructional design models are variations of the ADDIE process. To read more on the various instructional design models, click here.

Key Lenses for effective Instructional Design

There are three key lenses for great instructional design that also guide learning-design thinking and decision-making:

Learner-Centered

To be learner-centered is to design while focusing on fulfilling the learner’s needs and desired outcomes. In Seductive Interaction Design (2011), Stephen Anderson describes the “Learner Hierarchy of Needs” (see Figure 3). As in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1943, 1954), the base of the pyramid is essential and must be present to successfully support the next level. Once an individual fulfills one level, they look to the next level of fulfillment. For example, in the Learner Hierarchy of Needs, learners need to log in (functional), but they also need the site to have excellent uptime (reliable). When designing for learning, many may stop at “convenient”—meaning that students can log in reliably, they can use the course without difficulty, they can find what they need, and they know where to submit assignments. Students can even use the course across multiple devices and access it anytime, anywhere: it is convenient for their lifestyle. Indeed, these are all important and fundamental aspects of excellent, learner-centered experiences.

But the pleasurable, meaningful experiences represented by the top two levels of the hierarchy are where real transformation in identity and outcome occur. The exceptional instructional design never stops at convenience; it continuously strives toward pleasurable, meaningful learning.

To achieve exceptionality in design, designers must push for all levels of the learner hierarchy of needs to be met, stretching toward designing for those top tiers of the pyramid when creating assessments and activities and tailoring the structure for effectiveness. It is in striving for effectiveness (the ability to achieve learning outcomes) that designers draw upon theory and understanding of human learning, motivation, and key principles of instructional design.

For learning design to be effective, there must be solid instruction, activities, and opportunities for specific feedback, valid assessments, and clear objectives and outcomes, with strong alignment among them all. To be meaningful, the learning design should be relevant, authentic, and connected to students’ lives (which requires designers to know who learners are). To be pleasurable, the experience should lead learners to experience moments of pride, joy, or connectedness (to name a few positive results). All of these aspects of effectiveness require empathy with regard to learners, where they are, and where we want them to be. Most instructional design work resides in the “learner-centered” lens, but it should not stop there. To be exceptional, the second and third lenses must also be employed in practice.

Feasible

What designers conceptualise should be possible. This second lens of feasibility also means that when innovating, new ideas should not be discarded simply because they have yet to be tried. If the innovation is learner-centered and grounded in how people learn, and if the idea is feasible to accomplish given the context, it can be implemented and tested through a design thinking process.

Sustainable

Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. In other words, just because something is feasible, that doesn’t mean it is sustainable. Ideas can be learner-centered and feasible, but if an idea or design is not sustainable over time, it likely is not the best choice for learners or those responsible for facilitating it. Determining sustainability requires a deep understanding of and sensitivity toward context. For example, in one instance a group of instructional technologists may not have the capacity to edit and maintain certain types of interactives, whereas other groups may have the expertise, funding, and capacity. Each situation requires consideration of context when making design decisions, as decisions made now have both positive and negative ramifications over time.

Now we can start with designing and developing courses in a more structured way, to ensure that they are optimised for new forms of instructional communication, interaction, and engagement.

Design and Teach Your Course

Effective online instruction depends on learning experiences that are appropriately designed and facilitated by knowledgeable educators. Because learners have different learning styles or a combination of styles, online educators should design activities that include multiple modes of learning. Teaching models should also be adapted to the new learning environments. Many of the decisions affecting the success of a course takes place well before the first day of class. Careful planning at the course design stage not only makes teaching easier and more enjoyable but also facilitates student learning. Once your course is planned, teaching involves implementing your course design on a day-to-day level.

Design Your Course

Click on the link for each point to read further.

To design an effective course, you need to:

Write a Syllabus

View syllabus-specific information on how to:

Teach Your Course

Here you can find information on how to:

The quality aspect of designing your course will be further discussed in Module 4.

As teachers, we are learning designers and we must reflect on the current practices of teaching and learning to evaluate the effectiveness of the strategies used and engage in designing effective learning activities and experiences that encourage our students to use their knowledge in meaningful ways. In addition to effective design, we need to provide online learner support for student success in ODFL.

Project lead

Supported by

Development Partner